RENEGADE GARDENER™

The lone voice of horticultural reason

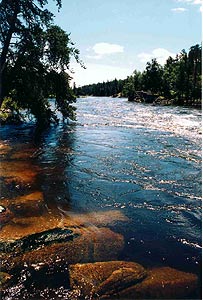

Lessons From the Wilderness

Near Minaki, Ontario

I like the way nature landscapes, and always come back from my treks through the Canadian wilderness having learned a few things about gardening and landscape design.

At least I believe I do, though it’s never the case where this fresh knowledge comes immediately into play. The images I bring back from my past three weeks exploring the woods, meadows, stream banks, waterfalls, cliffs, and shorelines surrounding the remote town of Minaki, Ontario, will steep awhile, then in the lifetime to come bring to my puny attempts at gardening a few faint flashes of graceful space that might honestly be deemed natural.

Native landscaping

In northwest Ontario, nature landscapes in broad, sweeping carpets of chaos, a misfiring whirlwind of botanical anarchy that is not so much painted as spewed. No careful, rule-guided placement of plants here. Instead, the native flora claim this granite ground as castaways, dispersed across the jagged territory like stumbling, blindfolded refugees. White pines, junipers, grasses, and the monstrously hardy native perennials cling to the shorelines and form their ragged plant communities as if survivors of shipwrecks.

Even toward the end of August, when many of the native shrubs, perennials and wildflowers are well past bloom, this is achingly gorgeous country. I hesitate to attempt to define the form behind this geographic beauty, to classify it in terms of rules. Perhaps I can express in words at least a few facts about this landscape that contribute to its astonishing splendor.

Fragrant Water Lily (Nymphaea odorata)

In the wilderness, nature is a cruel beast, and key to the beauty of this land is that liberal mankind has had little impact. This land is the result of design principles of the highest origin, explosive, selective, ruthless, resolute. What grows here and how it appears to me during my brief visit—how it appears to mankind during our brief visit—is ruled by wind and flood and fire. In the garden, we’re much too kind, bestowing a spritz of insecticide to protect a frivolous plant that doesn’t truly belong there from a marauding bug that doesn’t belong there, either. Above all we depend too strongly on man-made, elementary rules of design. Elementary, I’ve decided, is one step too advanced from nature.

In Ontario, first and foremost is the fact that trees and shrubs rule, adding credence to my contention that we humans plant far too many flowers. In typical American fashion, we’ve sold ourselves on a mutated garden landscape style that’s all colorful splash and panache, ramming blooming annual and perennial flowers into our yards in lock-step with the national dictum that more is always better.

Panicled Asters (Aster simplex) cling to the shoreline like shipwreck survivors.

We didn’t get this floral effusiveness from our English gardening ancestors, whose rules of garden design form the foundation of the present American gardening style.

Oh, the English gardens of the 18th and 19th centuries, through to today, were and are fabulous canvases of colorful flowers, certainly. But the flowers are in rather small proportion to the much grander canvas of trees, hedges, and blooming shrubs. (Americans, beginning in the 1950s, performed exactly the same mutation when it came to choosing the proportion of their properties to devote to grass lawns, but don’t get me started.)

When I gaze across the Ontario wilderness, it’s abundantly clear that key to its beauty is the principle that less is more. The lazy pockets of goldenrod (primarily Solidago canadensis and S. ohioensis) now in golden-yellow bloom tumble across open areas in fits and starts; beautiful, yes, but always second fiddle to the ever-present foundation planting of native juniper, pine, spruce, tamarack, birch and poplar. Here, floral color becomes precious accent, its beauty all the more alluring than if flooding across as gross masses of color.

Island Bed

Thinking of my perennial gardens back home, I realize that for years I have attempted to wring beauty by planting and fertilizing entire beds of flowers, flowers, and more flowers. In a sense I’ve enabled little more than the floral equivalent of a loud, drunken mob scene. I’ve tried to create stylish grace in my gardens by ramming color in your face. You’d think I’d learn; this wilderness lesson had presented itself to me once before.

Years ago, in the spring, at the end of Big Sand lake far north of Minaki, I came upon a lone clump of a bog iris known as Larger Blue Flag (Iris versicolor) halfway down a quarter-mile stretch of wilderness, white-sand beach. There was a large swamp running parallel to the beach about twenty feet inland; heavy rains had caused the swamp to rise, and at a single point, a tiny trickle of bog water had cut through the sand to join the lake below. The iris, or a seed, had escaped the swamp via this temporary passage and rooted itself smack on the beach. I was witnessing one of the most exquisite jailbreaks of all time. Exposed to full sun, the iris burst tall in lush, radiant bloom. Snooping about the shady swamp area farther inland, I spotted more Larger Blue Flag, but none had flowers so numerous or vibrant as the escapee celebrating its good fortune down on the shoreline.

Canada Hawkweed (Hieracium canadense)

And how much more glorious were its perfect, violet and yellow-throated blooms as it stood in sunny, solitary independence, than if the entire shoreline were to be choked full of its brethren, as far as the eye could see!

In this case, the iris proved the exception to the rule, for the beauty of this wilderness is that rarely do plants grow alone. The cool blue blooms of Harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)seem to float in air amidst gentle clumps of slender grasses, and above a lazy groundcover that might include three types of moss and five other low, matting plant forms. This time of year, Canada Hawkweed (Hieracium canadense) is in bloom everywhere, bursting yellow from stumps, meadows, pathways and the woodpile. But it is never alone; upon even cursory inspection, one notices the Hawkweed raising hell with no less than a dozen other plant varieties, blissfully butting heads, busy creating a crazy quilt.

A journey of 500 miles due south has brought me home to Deephaven, Minnesota. Coming up the driveway I spot my impatiens bed—impatiens only, if you please. And in a large herbaceous bed I find my polite three clumps of sedum, in front of a carefully edged swath of boltonia, which ends abruptly (and is spaced safely) lest it interfere with the exacting domain I’ve assigned to the fall asters. These and ten other varieties of perennials and annuals grow in the same bed, yet now I see that they barely coexist.

Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis)

So what is the lesson, the answer? Cottage gardens? No—not even the most fertile meadow creates such a gangly mess of flowers. We’d be dealing with drunken mobs again, and besides, there isn’t enough Daconil in the world. No, we need to take a strong look at proportion.

Why do many of the smaller city lots, and I’m thinking of the Kenwood and Lake of the Isles neighborhoods, contain such beautiful landscapes? Look closely—half the front yard, sometimes more than half, is dominated by trees and shrubs. The color from the narrow flower beds that seep from the edges serve the same role as does a colorful tie accenting a killer suit, or throw pillows on a magnificent sofa. Proportion.

I must experiment with scattered plantings. Certainly the booming trend toward landscaping with natives will continue to be an important factor in this regard. But must we abandon our exotic favorites, our tropical annuals, Asiatic lilies, and European-born perennials? No, but I think we should loosen up a bit, reexamine our rules of planting in groups of the same variety, ponder why beds need to be contained and defined, and why huge lawns always run up the middle (or why they exist at all).

There is much, much more that I have learned this trip. A purpose may be served some day. Not all of it has come to me yet.

Lessons from the Wilderness II

Gardening affects gardeners more than we know. It has to do with the omnipresent nature of topography, I suppose, the inescapable imposition of landscapes. Few hobbies offer such an affront. An avid golfer doesn’t drive to work and think, “Gee, noticing this stretch of road and the bend ahead, I wonder if I could just tail a four-iron to exactly follow the pavement.” Fly-fishing fanatics don’t revel in the thrill of their sport when out walking the dog.

But a gardener gets in the car to return the videos and pick up milk, drives half a block, and thinks, “Ooh, does that old oak in the Carlson’s front yard ever need a good trimming!” Walking to get the mail, we check out the new Heuchera in the corner of our neighbor’s plot. Riding in a taxi from the airport after landing in another part of the country, we study the trees comprising the horizon, and look closely at the shrubs used to landscape the freeway cloverleafs. We make notes to ourselves, things like, “Sure enough, concrete retaining wall block looks like hell in Texas, too.”

We garden the planet Earth. The thirst for knowledge that is gardening, and the aesthetic opinions that this knowledge imprints, automatically kick in every time we view the outdoors. It kicks in hardest for me when I travel to north Ontario, from where I recently returned.

In the final week of May it’s cold on this granite island three miles down the Winnipeg River from the tiny bush town of Minaki, Ontario. It has been cold all spring. We get in late, across deep, black water, to a forty-one-degree cabin, so the first duty is a roaring fire. It barely knocks the chill from the air. I have forgotten soup, the customary first supper, remembered hotdogs, but forgotten bread, and ketchup. So we dine, near midnight, a hotdog bare on a paper plate, Ovaltine, a banana, Rugrats fruit snacks for desert. I snuggle under a thousand blankets and sleep as I only do in Ontario, deep, effortlessly, and without dream.

In the final week of May it’s cold on this granite island three miles down the Winnipeg River from the tiny bush town of Minaki, Ontario. It has been cold all spring. We get in late, across deep, black water, to a forty-one-degree cabin, so the first duty is a roaring fire. It barely knocks the chill from the air. I have forgotten soup, the customary first supper, remembered hotdogs, but forgotten bread, and ketchup. So we dine, near midnight, a hotdog bare on a paper plate, Ovaltine, a banana, Rugrats fruit snacks for desert. I snuggle under a thousand blankets and sleep as I only do in Ontario, deep, effortlessly, and without dream.

The next morning at sunrise I walk the woods and cliffs and shorelines and at first am disappointed by what I see, or fail to see. Spring has barely arrived, and few wilderness flowers are in bloom. Last year at this time it was eighty-two degrees, and everywhere you looked there was color. Carpets of white curled through the woods, the baton traded between Nodding Trillium (Trillium cernum), Bunchberry (Cornus canadensis) and Star Flower (Trientalis borealis). The pink-purple petals of Wild Geranium (Geranium maculatum) edged nearly every portage and path. Trout lilies (Erythronium americanum) shown their bright yellow faces atop elegant, slender stems nearly anyplace a fallen tree or rich depression cast enough soil to support life. I didn’t have my camera.

Maianthemum canadense (Wild Lily of the Valley)

Now as I walk I’m already thinking of ways to juggle my duties and commitments at home in order to sneak back up here in two weeks. But wait. Here’s something. A lone Wild Lily of the Valley (Maianthemum canadense) greets me just as the sun begins filtering through a swath of aspen and pine forest. These things don’t grow alone, there will be hundreds, thousands of them here soon, but this one is apparently a real go-getter.

The white flower buds have formed but not opened; still, the plant is perfect sculpture. From the elegant, subtly twisting, copper-colored stem float two leaves held in effortless balance, though the bottom one is larger. The tiny, clustered flowerhead is poised exactly in the middle of the line the eye draws between the tips of the two leaves. The visual weight, the angles, the scale of every component of the plant is perfect. It’s fantastic art, effortlessly flaunting the design principles flower arrangers hone during a lifetime. Over the next six days, it remains the only one I see.

Corydalis sempervirens (Pale Corydalis)

Then on a rocky shore I am greeted by waves of Pale Corydalis (Corydalis sempervirens), nodding clusters of pink flowers tipped with yellow, bobbing and weaving in the wind like bobble-head dolls. On the same shore I find Great-Spurred Violets (Viola selkirkii) in abundance, and once I see them I see them everywhere. They grow in clumps out of moss-covered granite, there is no soil to speak of, yet have survived this region’s Zone 3 winters for thousands of years. Now that’s a perennial.

Soon I realize that since this is such a late spring, I’ve never been to Ontario this early in the season. For the first time I see moss in bloom — or is it past bloom? Singular, threadlike, reddish stems hold pale green pods two inches in the air. Slicing one open I see it holds seeds; so it is past bloom. How long has moss been on the planet? A million years? Who knows? One thing is for certain, it sure gets an early jump.

Viola selkirkii (Great-Spurred Violet)

The early jump I’ve made this year is proving to hold some advantage. Not thirty feet from the cabin I spy a sprawling, amazing groundcover I have never seen before — it becomes hidden later in the season. Needle-like leaves of the softest green are tipped in white along spreading branches that measure five feet out from the mother plant. Is it Crowberry (Empetrum)? I wish I could see it in bloom, if it blooms per se. If the nursery industry ever got their hands on this it would fly off the shelves. Hopefully, like so many plants up here, it won’t grow in anything resembling friable soil, and will remain a wilderness secret.

Temperatures rise as the week progresses, and on our final full day we embark early for a lengthy fishing trip to the Dalles. The Dalles is a slim granite chute fifteen miles upstream where the entire Winnipeg River is rammed into two narrow channels. The water is very high this spring, and as we near the Dalles the current causes the water to roil. We catch nothing but perch, and no matter where we fish, in the current, off the current, in shallow bays, off deep and shallow reefs, I cannot find a walleye. The more I fish in Ontario, it seems the less I know about fishing.

The sun is warm, the wind has ceased, and a few miles downstream from the Dalles we go ashore to stretch our legs and have a look about. I have landed on one of fifty islands I might have chosen. This one is particularly out of the way, as we had been miles off the main channel, fishing in bays. I should point out that the Winnipeg River is not a river in the classic sense. It is a nearly infinite, granite-lined maze of islands, points, hidden lakes, channels, and bays, all flowing North, where its waters will join the mighty Nelson River and finally dump into the Hudson Bay.

The sun is warm, the wind has ceased, and a few miles downstream from the Dalles we go ashore to stretch our legs and have a look about. I have landed on one of fifty islands I might have chosen. This one is particularly out of the way, as we had been miles off the main channel, fishing in bays. I should point out that the Winnipeg River is not a river in the classic sense. It is a nearly infinite, granite-lined maze of islands, points, hidden lakes, channels, and bays, all flowing North, where its waters will join the mighty Nelson River and finally dump into the Hudson Bay.

The only reason I chose this island was that it had a tuft of brush rising from a V-shaped patch of soil at the shore, where I could nose in and tie my boat. It’s a small island, about an acre, a granite crown tufted with birch, spruce, red and white pine, junipers, grasses, and a dozen varieties of mosses. My son Elliot disappears over a granite crest, excited to be free from the confines of the boat and the boredom of lousy fishing.

Cypripedium acaule (Pink Lady’s-slipper)

Soon he gives a shout. Though only ten, I rely on him as my chief flower-spotter. “Dad, come look! Really weird! Really cool!” I follow his voice to the other side of the island and as I approach I see them. There they are, there’s the prize, the jewel, one of the neatest catches you’ll find in the northern wilderness: Cypripedium acaule, the Pink Lady’s-slipper, or Moccasin flower.

Before me is a clump of two, rising like royalty from the brittle white moss. Then another two, then a clump of six, and over there, eight. How many years has it been since a human has stood here and been silenced by their beauty? Ten? A hundred? Ever? No matter; they bloom just for us this year, for there is no chance another angler will happen on them before their mesmerizing blooms fade, in just a few precious days.

Groundcover (Empetrum?)

We arrive in late afternoon to the cabin, to discover it has been under assault since moments after we left at dawn. Armyworms (Pseudaletia unipuncta) are everywhere, everywhere. The dock, the deck, the screen doors, every tree and shrub on the way up to the cabin, on the clothesline, the woodpile, the water tank. They broke with today’s heat, and as I look up I can see hundreds of them rappelling down from the trees.

The next morning they are so thick around the cabin you can hear them. Though they prefer the deciduous leaves of aspen, they have already defoliated pretty much everything they’ve landed on, including young pine. Walking around the cabin as we prepare to leave we swing sticks back and forth like swords, yet still come inside covered with worms, and their silk.

The assault begins!

And I leave them to it. This is their gig; I’m just a freeloader. Across northern Ontario the aspen are going to get clobbered, and many will die out, leaving open spaces for the young spruce and pine to flourish. I’ve seen the cycle twice in my forty-four years. While I’m alive or well after I’m dead, a fire will clear out the pine and that next spring the aspen will again take command. It has happened many times, over thousands of years, and there is no reason for me to react. My little blip of breath in the context of the lifetime of this wilderness is of no greater importance than the life of the beaver in the next bay.

I return to civilization, to deadlines, to phone messages and in-boxes, again reminded that my petty concerns and exaggerated needs are childish and ephemeral. There is no need to return in two weeks, I have seen what I need to see. I will wait and return to Minaki in August, and am quite looking forward to it.

Lessons From the Wilderness III

I don’t know for certain that gardeners have a greater appreciation of wilderness areas than do non-gardeners, but I suspect we do. After all, we’re intrigued by the acts of rearranging earth, of growing stuff up from it, and placing items on it. So it makes sense that gardeners cast perhaps a slightly keener eye on those views of the planet where, when it comes to the topography, the plants, and the accessories, only nature has had a hand. Who knows? There may be an idea we can steal.

|

| Symmetry |

When I travel, I know I’m always focusing on the view, even if I’m traveling for business and gazing only from the window of a cab on the ride from some airport to some downtown. Generic billboards, freeway bridges, factories, bits of neighborhoods, churches, schools, office buildings, always, but sometimes unmolested patches of forest and often water, and occasionally a view of enough miles off yonder that I get some sense of the natural topography of wherever it is I am. Still, it’s always a pity. I bet I’ve been to Georgia a half-dozen times, yet all I know is the freeway view from Hartsfield-Jackson Airport to downtown Atlanta, and that’s a shame. I hear Georgia’s pretty.

|

| Grace |

Sometimes I’m able to afford a few extra days on a trip, rent a car, burn up a few hundred miles. I don’t stop until I find wilderness, until I reach a place where the land, the sky, and the view these two create has since the beginning of time remained completely unfettered by human hand. Then I get out, grab my backpack, and walk, walk away from the road and emerge gently into the wilderness, taking no effort to make my pulse drop, my breathing to grow deep and steady, my body to slowly shrug off its tension, my mind to calm and open to new thoughts, new revelations, no effort required for any of this, the wilderness draws all human efforts, mental and physiological, from you.

|

| Persistence |

As I walk I look at the shape and flow of the earth that surrounds me, at the trees and shrubs, the groundcover, the water (if I find any), all the while trying to figure out why it is always so supremely beautiful. I creep up on the activities of the wildlife and eavesdrop on the conversations between the birds, I marvel at the random perfection of nature, then after awhile I come upon a comfortable temple within the wilderness, where I sit and rest and ponder what I consider important questions, and see if I get any answers.

|

| Peace |

It’s a habit. I’m out looking for a high, a mood-altering experience, not that much different from my drinking and etc. days, now decades past, except of course that these wilderness highs are good for me, and don’t make girlfriends so darn mad. This wilderness habit was developed early in my life, whereby the luck of geography and ancestry I have been able to spend some portion of every year of my life exploring the shorelines, islands, forests, cliffs, lakes, rivers and streams surrounding the tiny bush town of Minaki, Ontario.

One cannot experience this wilderness and not ponder whom or what created it, wonder why it so quickly infiltrates and alters every element of one’s being. Why are we drawn to wilderness? What power does it hold? The answer that has slowly formed for me is that we are drawn to wilderness because in areas where the influence of human, mortal man is nowhere in effect, the spiritual principles that lie beneath all material reality rise nearer to our perception.

|

| Beauty |

Ooh, careful, Don. Next thing you know you’ll be mentioning God and quoting the Bible, and that always causes half the people reading something to scurry for the TV remote. News Flash! The Renegade Gardener is a right-wing Christian zealot! No I’m not. But steep yourself in the wisdom of this Ontario wilderness for going on five decades and it becomes impossible to find credence in the arguments of the atheists.

|

| Beauty, Grace, Love |

They argue that all I see when I explore this land just simply happened, a big bang, some quirky, giant, non-sponsored chemistry experiment that by sheer chance created the most exquisite examples of beauty, grace, harmony, peace, persistence, supply, unity, symmetry and love I have found anywhere. Yes, love. I am immersed in love for this wilderness. Where does this love come from?

Is it some chemical released in the liver, or pancreas? Scientists have never found it. Is a mother truly the single source of the love she feels for her child? Or is the source something greater, something nearly inconceivable to human thought, some infinite source from which love passes to us?

|

| Design |

Study the photos—you don’t have to believe in a Creator or Supreme Spiritual Being to realize that there is masterful design behind this wilderness. Why can’t those of the “sheer chance” persuasion, who insist that the design of our planet and the universe had no designer, shift half a degree and call whatever sheer chance caused it all, God? I think the hesitancy has everything to do with the established, prevalent definitions of this word, “God,” and the human, erroneous idiocy that has been performed on His/Her/Its behalf.

Wipe the slate clean, and it’s not difficult to believe in God. One’s definition of God need not be remotely similar to anyone else’s, after all. God can be principle. God can be whatever unseen, intangible principle created this wilderness.

|

| Harmony, Beauty, Grace |

Truth is intangible, yet real, as is life. Did humans invent life? I can pick up an acorn from my yard, put it in my pocket, fly to England, go hike in the countryside, plant it, and 200 years from now there will be an eighty-foot oak tree growing in the English countryside. Aside from my courier service, did man have anything to do with that? Then what did?

These key principles that humans did not invent—truth, life, love—they aren’t material, yet are real, and came from somewhere. A common word for this unseen, alternative reality is spirituality. That word doesn’t offend or scare me. It intrigues me. It makes me ponder that perhaps the spiritual reality is the true version of our existence, and the material reality the false. It makes me ponder that as I gaze at this material wilderness, I’m actually glimpsing evidences of spiritual principles, and that as the version you choose to believe in grows in your consciousness, it becomes your reality—for better, or for worse. At the very least, I’ve arrived at the belief that when it comes to the material world, there’s more going on than meets the eye.

|

| Supply |

We look not at the things which are seen, but at the things which are not seen: for the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal.

Damn, my fault, should have warned you, II Corinthians 4:18. Some of you are thinking, what is going ON here, this is supposed to be a goofy gardening Web site. Well, sorry, I guess I’ve spent too much time in the wilderness, pondering man’s origin and existence. And yes, have checked out the Bible, I’d heard rumors it had something to say on the subject. Don’t flip. I’m on a quest, here, and the Bible happens to be one of the reference books I’ve found interesting. There are others. Put that remote down, you made it this far, I’m almost done!

|

| Peace, Unity |

In fact, that’s all. Thoughts on what draw me to gardening, to nature, to the wilderness. I believe that our material experience evidences spiritual principles that we can ignore or pursue, and you’ll find this evidence more readily in the wilderness, than in, say, downtown Manhattan. Look at this wilderness: beauty rules, grace abounds, harmony exists in every design, peace is present, persistence is a law, the river defines supply, unity and symmetry are in abundance, and love continuously unfolds.

|

| Unity, Symmetry, Love

|

And humans had nothing to do with it. If all mankind emulated only these qualities, I suspect the world might appear to us a much different place.

OK, I’ll play fair this time. WARNING: BIBLE PASSAGE FOLLOWS.

But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned.

— I Corinthians 2:14

These are the questions I ask, and the answers I receive, when I enter the spirit of the wilderness.

Don Engebretson

The Renegade Gardener