RENEGADE GARDENER™

The lone voice of horticultural reason

Top 10 Gardening & Landscaping Blunders — and How to Avoid Them!

2-1-07– Over the past several years this has become my most popular gardening program, both locally and when I am fortunate to give talks to gardeners in other parts of the country. Whether speaking in Minnesota, Pennsylvania or Oklahoma, I never provide handouts for the audience, of course—that would involve forethought and logistical planning—so what I’d like to do here is rip through my Top 10 list and let this article serve as the grand handout that I never quite get around to creating or disseminating.

2-1-07– Over the past several years this has become my most popular gardening program, both locally and when I am fortunate to give talks to gardeners in other parts of the country. Whether speaking in Minnesota, Pennsylvania or Oklahoma, I never provide handouts for the audience, of course—that would involve forethought and logistical planning—so what I’d like to do here is rip through my Top 10 list and let this article serve as the grand handout that I never quite get around to creating or disseminating.

Three important criteria in order for a blunder to make my Top 10 list: First, it must be a common blunder, as common as crabgrass, the same mistake I see homeowners making all around the country as I travel. Second, it must be a major blunder, it must impart true gruesome effect on one’s yard and landscape, or on one’s ability to grow a healthy plant. Third—and keep this one in mind throughout—it must be a mistake that I have made at least three times over the twenty-plus years I have spent developing as a gardener.

Here we go:

Thinking too small is when we look out over our property, and regardless of lot size, we see our yards as little segments, or individual areas. We want to grow some annuals out by the road at the start of the driveway, so we cut a little circle into the lawn and fill it up with zinnias, or something equally dreadful. Next we want to grow perennials, so we create a raised bed out of boards along one finite section of sunny fence, and boom, there’s our perennial garden. We decide the front of our house needs something so we plant a couple of shrubs near the front door.

Thinking too small is when we look out over our property, and regardless of lot size, we see our yards as little segments, or individual areas. We want to grow some annuals out by the road at the start of the driveway, so we cut a little circle into the lawn and fill it up with zinnias, or something equally dreadful. Next we want to grow perennials, so we create a raised bed out of boards along one finite section of sunny fence, and boom, there’s our perennial garden. We decide the front of our house needs something so we plant a couple of shrubs near the front door.

Thinking small leads to blunders like cutting little circles into our lawn and plunking stuff in them, such as a little wood wishing well. We circle lawn trees with stuff, uniquely American landscaping behavior; we have a perfectly lovely tree rising perfectly majestically straight up from the grass lawn, but we can’t leave it well enough alone, so we collar it with a tight little circle of plastic lawn edging, small fieldstones, bricks, concrete block, hostas, or daylilies (sometimes all of the above). These little clown collars completely upset any sense of visual flow that may have been present in the yard; when we circle trees we instead create individual little eyesores, and completely annex the trees from the overall landscape. I’ve written on this topic alone, famously, in The Astonishing Truth Behind Tree Circles.

We avoid this blunder by always looking at out property—the front yard, side yards, and back yard—as one unified whole. Whenever I walk through a properly designed yard/landscape, even one containing ample lawn area, as I walk from front to back and around the house, and over here and over there, I feel always as though I am walking through a single landscape. More on this when we come to Blunder #7.

9) We think too straight.

We let the straight-line dictums of human design, the straight lines of the street, the driveway, the sidewalk, the straight lines of the house foundation (as well as its ninety degree angles) dictate our landscape designs. Too often I see a planting in a front or side yard, whichever encounters the street, made up of one type of plant material, let’s say lilac bushes, running in a soldier-straight row, the line of shrubs exactly parallel to both house and street. The object of these mid-yard plantings is to shield or buffer the house, and its occupants, from the street.

Nearly every time I see these straight, single-species hedge-type plantings, the landscape is not calling for, nor are the homeowners interested in cultivating, a clipped, formal hedge. There is always ample room for this long, narrow, straight planting bed to have been installed as a series of graceful curves.

|

| 14 lilac bushes in a straight line. Why? What will supply midsummer bloom? Dazzling fall leaf colors? What will this look like in winter? (A row of gray sticks.) Where are the evergreens? |

And why just one type of shrub? Instead of fifteen lilac bushes in a straight line, why not make a gently curving, mixed deciduous and evergreen hedgerow of five or seven or ten different types of shrubs (and small trees)? Why not some randomly placed pyramidal evergreens, for winter interest, then a lilac or three, for spring bloom, mixed in with weigela, honeysuckle, or serviceberry, for midsummer bloom, plus dwarf burning bush or fothergilla, to add magnificent fall leaf color?

Why create a straight foundation bed along the front just because the house foundation is a straight line? Make the front of the bed curve. If installing a sidewalk or entryway, make it curve. Why plant things straight along the edge of the street, just because the street is straight? You may lack the wherewithal to change the street (or city sidewalk) into a curve, but you certainly have the power to curve the bed and the plants that run alongside it.

There are no straight lines in nature. There are no ninety degree or forty-five degree angles in nature. There are few, if any, perfect circles in nature (an Allium, or an Echinops bloom, is never a perfect circle, nor are eggs, ponds, or the eyes of an animal). Granted, there is a longstanding school of landscape design—English Formal—that is based on straight lines, ninety degree angles, circles, and impeccably clipped hedges. If what you are aching for in your yard is a classic English formal garden, go for it, it’s your yard. Done well they are magnificent, though high maintenance. Realistically, I find that ninety-five percent of homeowners are going to be happier with semi-formal or naturalized, informal landscapes that sweep and curve.

Nature backs me up on this. Nature landscapes in great rolling, arching swirls of topography. (You say Kansas is flat? Wait until you get to Colorado. The planet is one big yard.) Nature spews its plants across the land in swaths and flurries, a style of landscaping I call “random perfection.” We do well to study nature. (Further reading: Lessons from the Wilderness)

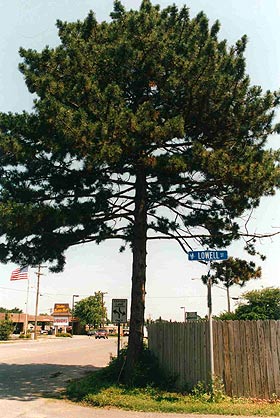

8) We’re afraid to cut down a tree, or rip out old shrubs.

Man, are we ever afraid to cut down a tree in America these days. We have this notion that the deforestation of the Brazilian rain forest is somehow related to that stupid spruce tree a prior owner planted six feet off the corner of the house. The two are not even remotely related.

If you have just bought an existing house, or if you’ve lived on the property for years, and this spring is when you are finally going to start developing a landscape, my advice is: Fix your tree situation first.

Walk your property and look at every tree, young, old, small, tall, and decide what you can work with, and what goes. Remove any tree that is on its last legs, diseased, storm damaged, ugly for any other reasons, planted in a dumb spot, grown too large for its spot, or in any way negatively impacts your ability to create the garden and landscape you envision. If you plant a tree for every tree you cut down, good for you, but if you cut down a tree and don’t plant one, that’s OK, too. Don’t take any guff about it from the twelve year-old kids on your street, or from their socialist parents, for that matter.

Same goes for shrubs. Shrubs rarely live their entire lives as attractive, functional components in the landscape. They get too big (although that’s a blunder on the gardener’s part, which we will come to), they get old and woody, and they eventually lose their health and vitality.

Common is that shrubs requiring full sun were planted in full sun twenty or thirty or forty years ago, and now the tree canopy has grown up. They’re growing over the last decade in shade. There’s no form of renewal pruning that will magically make your lilacs or weigela or spirea bloom in shade. Old straggly yews and arborvitae moping about, waiting another ten or fifteen years to die, are just going to look worse and worse. Rip them out, they sell these things at the nursery, go buy fresh new shrubs of a variety that will perform well in the property’s evolved state.

7) We devote too much space to lawn.

We never used to—at the turn of the century, and in the ‘20s and ‘30s and ‘40s, most Americans lived in cities, in row houses with little or no lawn area, and in houses on small lots with no more than fifty-percent of the property devoted to turf grass, usually less. What happened? The 1950s, and the great suburbanization of America.

We left the cities and developed the suburbs. Anyone could be a landowner, and buy a half or one or two acres of property, so we did, and we somehow became sold on this concept that now that we are landowners, we needed to surround our homes on all four sides with green grass. It’s to the point now where you look at a new home on a half-acre lot and eighty-five, ninety percent of it is turf grass. Here’s an example:

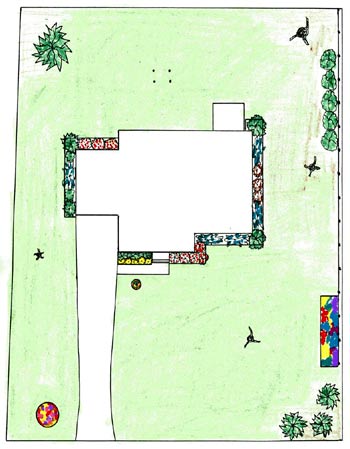

Here’s a half-acre lot with a house in the middle, the landscapers came in and circled it with a tight, straight, three or four-foot wide foundation planting, as is today’s status quo. Check out the back yard, perhaps the property is blessed with a lovely large spruce or pine in the back left corner, nice tree, never cut it down in a million years, but grass doesn’t grow well around it, and sort of peters out. Once children are born to the household, it’s time to plunk the swing set down in the middle of the backyard, represented by the four large dots. It’s tough to mow around, of course, and you have to go back each time with the hand trimmer and cut the grass down around the four legs.

Here’s a half-acre lot with a house in the middle, the landscapers came in and circled it with a tight, straight, three or four-foot wide foundation planting, as is today’s status quo. Check out the back yard, perhaps the property is blessed with a lovely large spruce or pine in the back left corner, nice tree, never cut it down in a million years, but grass doesn’t grow well around it, and sort of peters out. Once children are born to the household, it’s time to plunk the swing set down in the middle of the backyard, represented by the four large dots. It’s tough to mow around, of course, and you have to go back each time with the hand trimmer and cut the grass down around the four legs.

In the right rear corner, there’s a beautiful big oak, or maple, it shades that corner of the yard but creates a great canopy backdrop to half the house. A valuable tree. Moving from that tree forward toward the front yard, you encounter that shady side yard where you never can get grass to grow. Now check out the front yard, all the way out to the street by the driveway—there’s the little circle we cut into the lawn during our first experimentation with gardening, the one we fill with zinnias.

The annuals seem to grow OK so the next year we get adventurous and decide to circle the black iron light pole at the start of the sidewalk with Red Hot Sally salvia. After a few years of annual success under out belt, we decide to try our hand at perennials. This time we jump across the front yard to the right perimeter and board up a rectangular area in a nice sunny spot alongside the fence, and boom, there’s our perennial garden.

We plant a crabapple tree in front, maybe another along the sunny side by the driveway, but as things develop, as we look at out yard and “landscape” from the street, and from inside the house, we think, you know, it just ain’t happening. This is not what I had hoped for from my gardens and landscaping.

The blunder we are making is we are devoting too high a proportion of the property to lawn. Look at this same lot with full landscaping:

All we’ve done here is establish the concept lines, the lines that were there all along. In landscape design, a concept line is that line that the eye sees and follows as it gazes at a landscape. Using old, limp rubber hoses, or what I use now, 100’ lengths of limp, 3/4” rope, we start at the back left, at that big evergreen in the corner, and begin to lay out the beds.

All we’ve done here is establish the concept lines, the lines that were there all along. In landscape design, a concept line is that line that the eye sees and follows as it gazes at a landscape. Using old, limp rubber hoses, or what I use now, 100’ lengths of limp, 3/4” rope, we start at the back left, at that big evergreen in the corner, and begin to lay out the beds.

Broad curves are preferable to little squiggles. We curve along the back, over to the large oak in the right rear corner, then continue down and through the shady side yard. Grass won’t grow there? Fine, so we install a shredded bark or stepping stone pathway. We place a redbud or pagoda dogwood or other type of semi-shade understory tree as the anchor to the rear right corner of the house, then create a nice shade garden to flow along both sides of the pathway.

As we emerge into the sunny front yard, with just a few more shrubs and a continuation of the concept line, there’s our perennial garden, still against the fence, but now a transition of landscape style while still a part of the continuous flow.

Over on the other side of the yard, our little circle of annuals? It’s also still there, but we pull a bed from farther up the yard, and welcome our crabapple tree into the party, then gently curve the bed toward the street, finishing it off with perhaps a little boxwood hedge, fronted by colorful annuals.

The black light pole deserves its own bed, not a little circle; one thing I always do when there’s a poured concrete sidewalk that determines the finite width of the foundation bed is jump a bed over to the other side of the walk, so that when guests enter the house from the driveway they walk through the landscape.

Note too how the foundation beds have been bumped out, and curved so that they are wider as they move front to back. We need some width so that we can attend to Blunder #6.

|

| Here’s a stone barbecue pad I did for a client where I used two types of stone and had some fun with the concept line. |

Oh, the swing set—swing sets, dog kennels, compost bins, benches, gazebos, birdbaths—these objects can be pushed out of the lawn area into the concept line. You can see the four dots that show the swing set. Now the play area, instead of being trampled lawn, can be covered with rubber mulch or shredded hardwood, to give a soft landing spot for the kids. (Hurray! The one proper use for rubber mulch.) Also note that now, the back yard is actually bigger—kids have room to throw a baseball or kick a soccer ball, and when mowing the lawn, you are no longer mowing around swing set legs jutting up from the grass.

This property is still two-thirds turf grass. That’s plenty. (Additional Reading: Landscaping 101)

6) We don’t use enough small trees and shrubs.

So if the mistake is we devote too much space to lawn, it follows that the real blunder is, we don’t use enough small trees and shrubs. Once established, devoting square footage to small trees and shrubs is no more time consuming for the homeowner than the amount of time spent watering, mowing, and fertilizing turf grass, and can be even less.

So if the mistake is we devote too much space to lawn, it follows that the real blunder is, we don’t use enough small trees and shrubs. Once established, devoting square footage to small trees and shrubs is no more time consuming for the homeowner than the amount of time spent watering, mowing, and fertilizing turf grass, and can be even less.

“Small trees” means trees that mature at 25’ or less, things like redbuds, and all the ornamentals—crabapples, pears, cherry trees. Also magnolias (in the north), mountain ash, fringetree, and tree-like shrubs such as elderberry. And of course it includes the wonderful world of the dwarf conifers, the smaller pines, firs, hemlocks and spruces that are so essential for winter interest.

These small trees, along with shrubs, are the plants that exist in that 25’ – 20’ – 18’ – 14’ – 10’ – 8’ – 6’ range, that are essential in bringing the height and roofline of the house down to perennial flower and turf grass height, with some sense of grace. The goal of a foundation planting is to nestle the house in nature. You nestle a house in nature through ample use of small trees and shrubs.

5) We plant the wrong plant in the wrong place.

When we plant a perennial, tree, or shrub, intuitively we sense the need to ask one important question: How tall is this thing going to get? That’s important to know when selecting shrubs to plant in front of a picture window.

When we plant a perennial, tree, or shrub, intuitively we sense the need to ask one important question: How tall is this thing going to get? That’s important to know when selecting shrubs to plant in front of a picture window.

What we fail to ask, however, is an even more important question, and that is: How wide is this thing going to get? You can’t plant a row of Black Hills spruce four feet from a fence, and six feet from the road. It looks cute for five years, but they are only go to do what they must do: grow twenty feet wide.

So how do you avoid this blunder? You read the plant tag, or ask at the nursery, or buy a good book. Yes, there are shrubs that you can control width via base pruning and shearing, but when it comes to trees (and a fair number of other shrubs), they are going to grow as wide (and as tall) as their genetics tell them to.

So know how wide a plant is going to get, in five years, ten years, and at maturity, then pick trees, shrubs, and perennials that won’t grow too tight for their spot.

4) We get suckered into taking the easy way out.

Americans will spend thirty-four billion dollars this year on plants, gardening products and services, and a growing portion of the industry that sells them to us is convinced that we are a bunch of overworked, stressed-out, attention deficit-disordered fruit baskets who have no time, no desire, and no ability to learn how to garden.

This is the marketing monster behind the great dumbing down of gardening in America that began ten years ago, and gets worse and worse every breath I take. We are exposed to a multiplying plague of insipid plants, products, and procedures designed to convince consumers that gardening is easy, that it takes little time, and that you don’t really need to learn all those fussy minor details such as soil preparation, planting procedure, pruning, propagation, pest control, watering, winter care, botanical Latin names of plants or, lord help you, design.

Fully half of the 200,000 words and 300 photos on this site are devoted to preventing you from falling prey to this blunder, so I’ll not contribute more here. Finish this article, then the next time you’re on the site, poke around.

3) We use too few containers, structures, art, accessories, and other types of non-plant materials.

3) We use too few containers, structures, art, accessories, and other types of non-plant materials.

Once the plants are in the ground, the fun begins. Now we get to decorate and accessorize our outdoor areas with the same spirit with which we decorate and accessorize our home’s interior.

- Containers – I call containers “the throw pillows of exterior design.” Yes, they add foliage and bloom color to hardscape areas such as sidewalks, driveway aprons, steps, stoops, decks and patios, but fling them gaily throughout the landscape. Use bowls of impatiens under the shady oak tree, mark the entrance to a narrow garden pathway with a colorful container, place an urn of blooming annuals on a pedestal in the middle of the perennial or shrub border.

- Window Boxes – Another simple accessory, pulling the garden right up so that it kisses the house.

- Art/Sculpture – We buy art for our homes, now we can buy it for our yards. A great opportunity to support a local artist.

- Fountains/Water Features – Fountains and small, self-contained water features add subtle movement and gentle sound to the garden, in addition to soothing visual impact. It must be getting late—the preceding sentence sounds like I’m writing some dreadful article for Horticulture. I’ll try to snap out of it.

- Boulder Outcroppings – Anything that isn’t a live plant is an accessory, and stone outcroppings are in my mind an essential component to the naturalized landscape. As a landscaper, another thing I like about stone outcroppings is that stone doesn’t die. Plant material I use in your yard, I guarantee it for a year. Boulders I install, however, come with a written, 10,000-year guarantee.

- Benches, Arbors, Trellises, Gazebos – Consider them functional furniture pieces. Remember, they add winter interest (as do fountains and sculpture). Push them inside the concept line.

2) We don’t test, correct, and amend our soil.

Ninety-five percent of your success or failure as a gardener hangs on the quality of your soil. If you’ve never had a soil test, get one, or three, particularly before investing hundreds or thousands of dollars on plant material.

And don’t take the easy way out (Blunder #4), by purchasing one of those do-it-yourself soil-testing kits from the garden center. You want a lab test. Contact your county extension office to find out if your state university agriculture department does lab soil tests. Most do. If they don’t, they’ll have a list of local private soil labs they recommend.

Your country extension office will also answer all your questions concerning the test results—what to do to turn your dirt, sand, or clay into good gardening soil. It will involve some time, expense, and work on your part. In extreme cases, it may even involve prepping beds one year, and planting the next. Whatever it takes, you do it. This is called gardening.

Leads us all the way down to the big number one, the most common and important gardening and landscaping blunder:

|

| Beautiful garden? Of course. Hint: You’re not sensing beauty from bloom color. |

1) We design and plant garden beds based on flower color.

…and for this one I’m taking the easy way out. Read this: The Secret to a Beautiful Garden

BONUS BLUNDERS:

Depending on where and what time of year I am speaking, there are a few additional blunders that crop up on my list, at the expense of some of the above. Here they are:

We cut live, healthy limbs from our evergreen trees.

Don’t do this. Ever. Myriad reasons. Trust me.

We forget about winter.

We forget about winter.

Primarily a northern blunder, it’s good to keep this one in mind wherever you garden. You need to use a decent amount of trees and shrubs (and stone, and accessories) that add color, texture, and form to the winter landscape. Use ample evergreens, that’s the first rule. Evergreen foliage includes many shades of green, but also blue, grayish-blue, silver, and yellow. Use deciduous shrubs that have vibrant winter stem color, and/or good sculptural form after the leaves have fallen. Use small trees with cool bark. You do some research, you’ll find them. There’s only a zillion.

We plant our annuals too far apart and our perennials too close together.

The spacing instructions that come on those little annual plant tags are written for gardeners in Texas. In USDA Zones 2-5, ram annuals together a third to a half as close as the tags say. The northern growing season for annuals is five, six months. Spacing begonias, impatiens, or salvia twelve inches apart, they’re going to finally fill out and start touching leaves right about the time the first fall frost wipes them out.

On the other hand, when it comes to perennials, we want our cottage garden, and we want it now. Remember, perennials are bigger engines than annuals, they have deeper, wider, and denser root systems, and they need room to hunker in and grow. Most perennials need to be spaced around eighteen inches apart; many larger perennials are best planted twenty-four or even thirty inches apart.

Don Engebretson

The Renegade Gardener